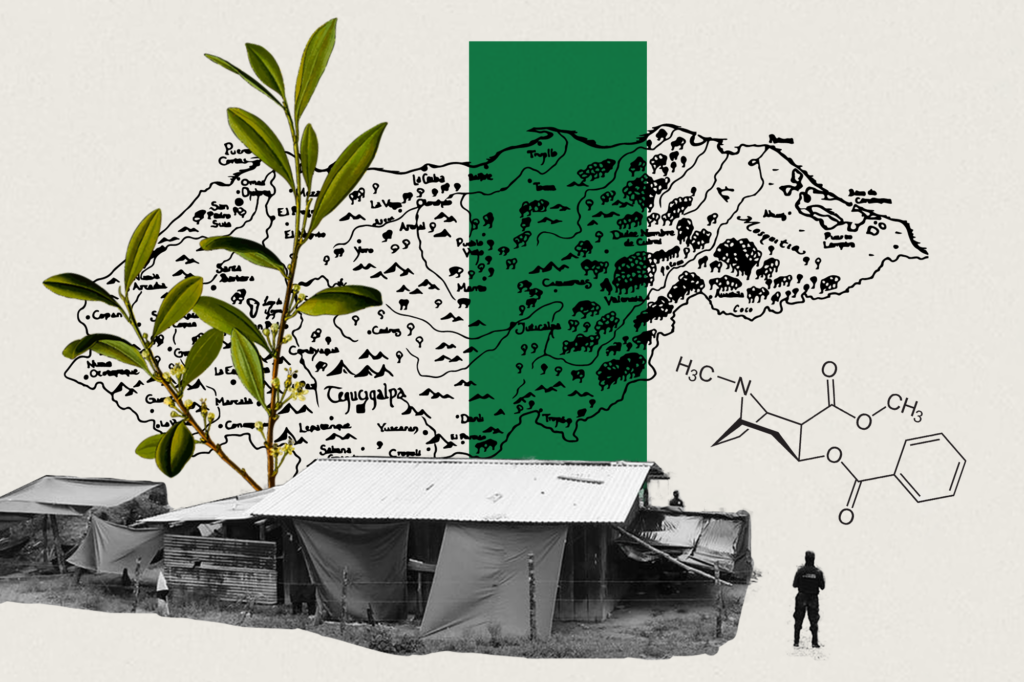

Honduras went from being a transit hub for drugs to producing cocaine. Over the last ten years, the municipalities of Iriona and Limón, Colón department, have headed the list of locations where security forces destroyed coca plantations and cocaine laboratories. In the rest of the country, Honduran cocaine has boosted a precarious and impoverished market.

Text: Célia Pousset

Photography: Fernando Destephen y Jorge Cabrera

Illustrations: Daniel Fonseca

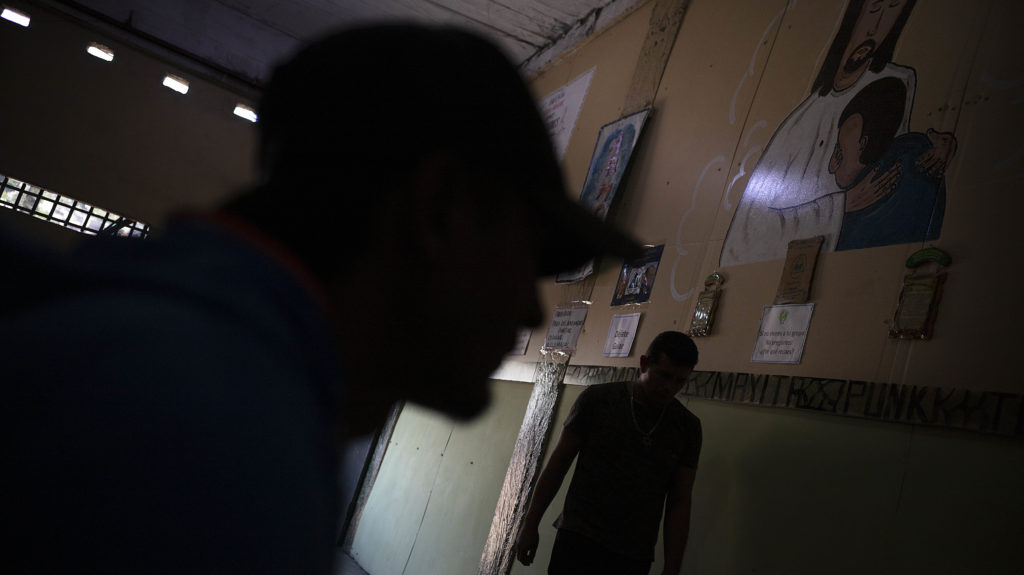

Smoking crack is inhaling fear and getting addicted to the panic. That’s what White, Ángel, and David say. The three men staying in a group home in Comayagüela, the impoverished twin city of the Honduran capital, Tegucigalpa, share something in common. One day, they tried “the rock” — another name for crack — and were hooked immediately.

Crack is derived from cocaine, mixed with baking soda and water, and burned in a spoon. This produces a rock that can be smoked in a pipe. In Honduras, it is frequently smoked using stolen car antennas. It is the cocaine of the poor.

Four hundred kilometers away, in the coastal Caribbean department of Colón, residents say their lives are surrounded by drug trafficking and fear. Authorities have eradicated more coca crops there over the past decade than in any other department.

Despite the distance separating Comayagüela and Colón, both places tell the story of a country caught in the grip of drug trafficking. In ten years, Honduras went from being a simple drug transit corridor to being a cultivator of coca plants and a producer of cocaine of dubious quality. That cocaine stays in Honduras, feeding local consumption, according to police sources.

Comayagüela: Resisting the Call of the Rock

Ángel sits on a plastic chair in the main room of a home for alcoholics and drug addicts. He begins by saying that he “wasn’t like this before.” He used to be fat, but crack made him lose weight. He is 29 years old, a former bricklayer, and has four children who he does not see much. He says he was not only a crack user, but also a drug courier for the Mara Salvatrucha (MS13), which controlled the drug business in his neighborhood.

Ángel started using crack at the age of 16 after a breakup with a girlfriend. He bought up to 3,000 lempiras (about $122) worth of the drug per week, even though his salary as a bricklayer was only 500 lempiras a day ($20). In Tegucigalpa, one rock — which produces one minute of “relief” — costs between 50 and 70 lempiras ($2-$2.83). Ángel consumed about 50 rocks a week, or one every three hours.

He soon ran out of money and began stealing drills, grinders, and saws from his job to buy crack. After he lost his job, Ángel started moving drugs to different parts of Tegucigalpa for the MS13. He did this for three years until the gang proposed that he officially join their ranks. Ángel rejected the proposal, but later understood that it was an order, not an offer, as he already knew too much about the business. He fled Tegucigalpa to avoid being killed.

Ángel went to the south of Honduras, settling in a city where he didn’t know where to buy crack. To feed his addiction, he instead started eating cocaine, as sniffing it didn’t have the same effect as crack. But cocaine was expensive, with one gram selling for more than 100 lempiras ($4). Plus, it never “scared” him like crack did.

Within months, Ángel found crack in Choluteca and after a few years, he learned that the MS13 members who threatened him had been killed. He decided to return to the capital.

Colón: Drug Traffickers, Coca Plantations, and Laboratories

The municipality of Limón in the department of Colón sits near the western end of the Moskitia, the jungle that covers much of eastern Honduras. Palm oil farms can be seen along the dirt roads that crisscross the area. Extending hundreds of hectares, these farms belong to powerful agribusiness entrepreneurs such as the Facussé family, owners of the Dinant consumer products company. Further in the backcountry, in the mountains of Limón, coca crops are hidden.

For decades, drug traffickers have disputed this area. It is a crucial arrival point for boats and planes laden with Colombian cocaine. Several Indigenous communities with claims to the land have had to fight to wrest it from the hands of drug traffickers who use the area for warehouses and logistical hubs. Now, in addition to frequently crossing paths with cocaine traffickers, Indigenous communities around Limón have to weather a coca cultivation boom.

Around 2010, Colombian drug trafficking groups began experimenting with coca cultivation in Honduras with the support of Honduran criminal groups, according to a former agent of Honduras’ National Anti-Narcotics Police Directorate (Dirección Nacional Policial Antinarcóticos – DNPA), whose identity Contracorriente is protecting for security reasons.

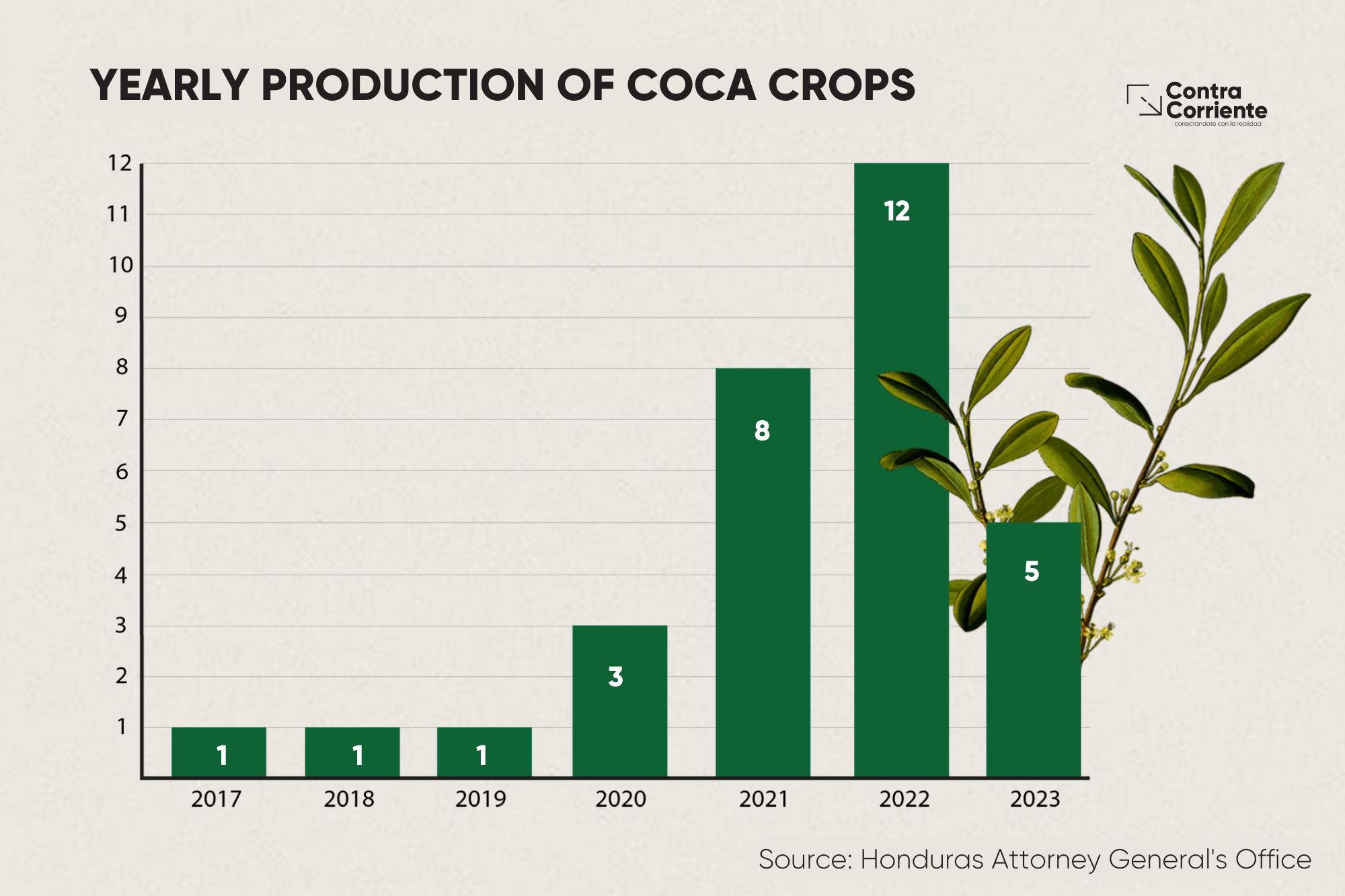

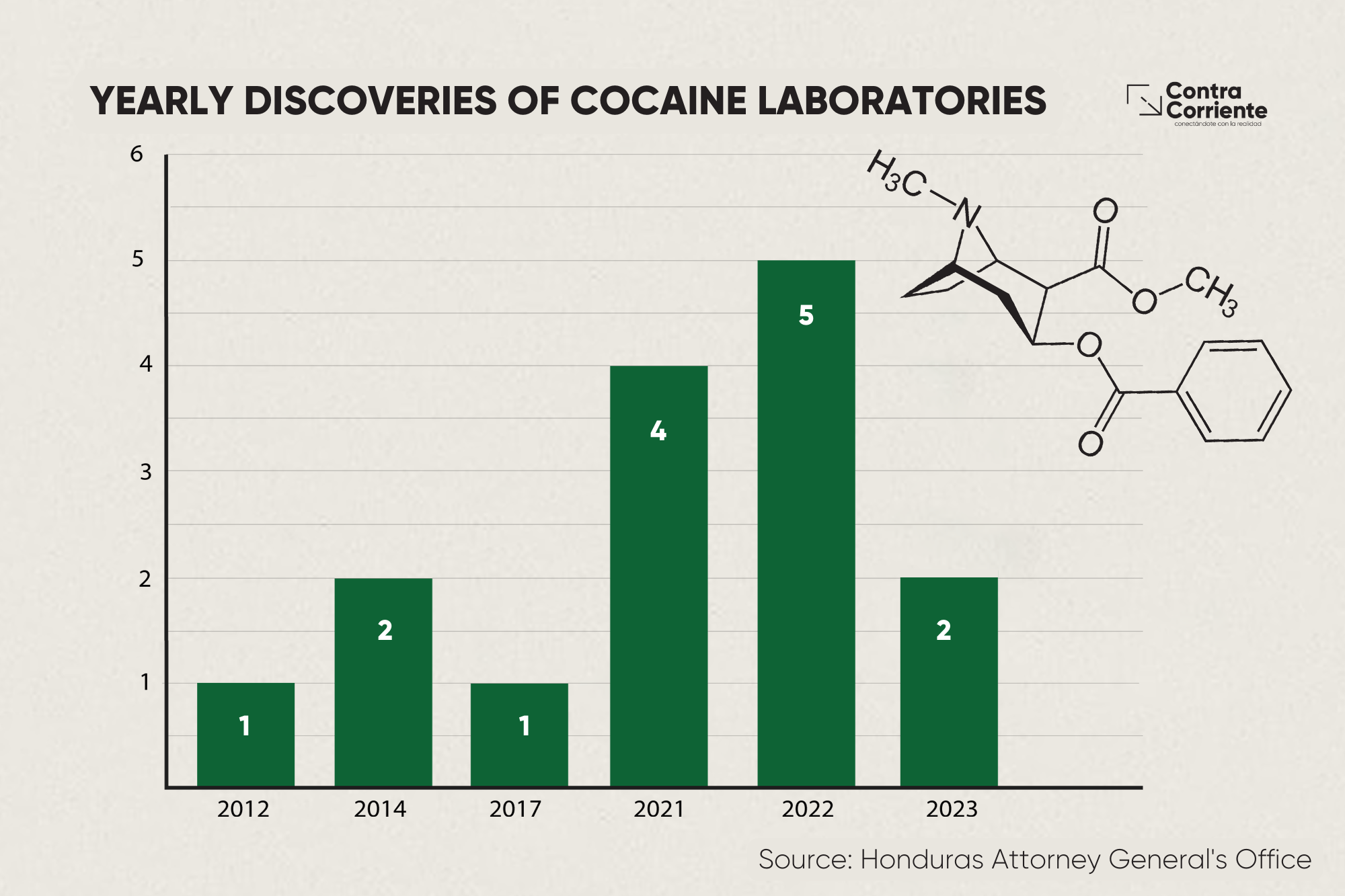

The DNPA, created in 2018, found the first coca plantations in early 2020, mostly in the municipalities of Iriona and Limón. The DNPA was created too late, according to the former agent, who cited the fact that other authorities such as the armed forces had already discovered coca crops in Honduras as far back as 2012.

Between 2012 and 2023, the Honduran Attorney General’s Office found 42 coca farms and 15 narco laboratories, 47% of which were in the department of Colón and mostly located in Limón. Data from the DNPA confirms the problem. Data from the DNPA shows that between 2020 and 2023, 28 coca farms were eradicated, and 28 drug laboratories were dismantled in Colón, 47% of which were in the municipality of Limón.

In a country whose former president was extradited to the United States on drug trafficking charges, the emergence of coca cultivation is in many ways not surprising. The advantages of coca cultivation in Honduras, however, were not always obvious to drug traffickers. Transshipment was their sole focus.

When Honduran drug trafficker Geovanny Fuentes came up with the idea of setting up his own narco laboratory in the country, he did not receive the support he hoped for. A wiretap that served as evidence in Fuentes’ trial in New York exposed how Leonel Maradiaga, leader of the Cachiros criminal gang that operated in Colón, did not want to collaborate with him because he felt it was cheaper to bring in finished cocaine from Colombia. Maradiaga argued that it was more profitable to simply move the drugs from Colombia to Mexico instead of producing them.

Despite skepticism from the beginning about coca cultivation in Honduras, today it is clear that the gamble was a success. At the national level, from January to August 2023, 3.5 million coca bushes were eradicated.

“About ten years ago we did not imagine that coca would be cultivated in Honduras, today we are seeing huge plantations,” General Juan Manuel Aguilar Godoy, director of Honduras’ National Police (Policia Nacional De Honduras), told Contracorriente.

The coca leaf must be processed within 12 hours after harvesting so that its active component is not lost. Therefore, at the edge of the plantations, there is always a rustic building, called a “laboratory.” Here, the coca leaf is chopped and mixed with gasoline, calcium carbonate, and water to release the coca alkaloid. The result is known as cocaine base paste or cocaine sulfate. In this form, it can be transported to any part of the world where there is a crystallization laboratory equipped with presses and microwaves to extract the moisture, and with chemicals to convert the paste into a powder called cocaine hydrochloride.

The only problem with Honduran cocaine is that it is of “poor quality” and therefore mostly serves to supply the domestic market, according to various police sources.

‘The Labs Are in Rich Neighborhoods‘

As a drug courier for the MS13, Ángel was familiar with some of the crystallization laboratories in Tegucigalpa. It was his job to pick up drugs and ship them to different points of sale. One of the labs was in Altos del Trapiche, a luxurious residential area in the capital city.

“Honduras has crystallization laboratories, but so far none have been seized,” the DNPA source said.

“We know this from intelligence information, but there have never been any operations. These laboratories are more difficult to find because they can be in any house and in any city,” he added. He also said that “in these laboratories, the cooks are almost always Colombians.”

Although the DNPA has never dismantled a crystallization laboratory, other national police units have. For example, the anti-gang unit of the national police seized more than 10 kilograms of cocaine linked to the MS13 in an operation to dismantle a “narcolab” in a wealthy residential area of Honduras’ second-largest city, San Pedro Sula. Similarly, a woman hiding 36 kilograms of precursor chemicals in her home was arrested in Altos del Trapiche in 2016.

White, 36, is a former plumber and ex-crack addict. He knows the process of transforming cocaine well, having learned how to cook crack from cocaine.

“The Maras and gangs control the business. They buy, for example, 50,000 lempiras ($2,020) of cocaine, turn it into crack rock, and make three times as much money.” He said that both the Barrio 18 gang and the MS13 have laboratories.

With drug selling territories strictly divided between gangs, the danger for crack consumers is knowing who to buy from and never making a mistake.

“You have to buy from the structure that controls your neighborhood because if they find out you bought from another point they can kill you,” White said.

Little is known about the links between the criminal organizations involved in drug trafficking and the gangs like the MS13 in charge of drug dealing.

Underneath the Coca, the Land Is in Agony

In recent years, coca crop eradication operations have become recurrent, but they rarely result in arrests. Drug traffickers use land that is difficult to access, and it is often impossible to trace the owner of the land, according to the DNPA source.

When authorities arrive by helicopter to coca farms, workers have often already fled. Compounding authorities’ troubles, they frequently must uproot the bushes – which can be up to 1.5 meters long – by hand. To uproot eight manzanas (a measurement of land equal to about 0.7 hectares) of coca plants, it takes between a week and 15 days, as each manzana has an average of 7,000 bushes.

Manual eradication is the most ecological way to uproot coca, but the plant is far from environmentally friendly.

“Coca is very profitable since it is harvested four times a year,” said a biologist who asked to remain anonymous for fear of reprisals. “But to obtain these results, you have to fertilize a lot by applying herbicides and pesticides. It deeply damages the soil. After about fifteen years of intensive cultivation, the land becomes infertile and irretrievable.”

The biologist previously lived in a region of South America where coca cultivation is common. We asked him how this Andean crop has been able to grow in Honduras’ tropical climate. Iriona and Limón are near the Caribbean Sea and the mountains in the area reach only 720 meters above sea level at their highest point, a drastically different environment from where coca thrives in the Andes.

“The plant underwent a genetic modification. It is a natural process, but it can also be done in laboratories to adapt it to different conditions. It is a cheap process but it takes time,” the biologist explained.

The biologist cited Peru as an example. Coca used to be grown in a region known as the “jungle belt,” an area located between the highlands and the jungle. Here, between 1,000 and 2,000 meters above sea level, coca was able to reach its full genetic potential. However, in order to escape law enforcement crackdowns and because the soil became worn out, farmers moved coca crops to lower altitudes, sparking adaptations in the plant.

In the part of the Peruvian Amazon where the government eradicated coca twenty years ago, the alternative for farmers was the African palm tree, the biologist highlighted, the same tree that expands over dozens of hectares in Colón.

From Cultivation to Consumption: The Cycle of Fear

Colón is one of the most violent departments in Honduras due to agrarian conflicts and the deep-rooted presence of drug trafficking. Between 2013 and 2023, 2,154 homicides were committed, according to Honduras’ Security Ministry (Secretaría de Seguridad).

The Honduran Network of Women Human Rights Defenders (Red de Defensoras de Derechos Humanos) also provides useful statistics on violence. Their report on incidents of aggression against women defenders revealed that, in September 2023, 78% of aggressions against women human rights defenders occurred against those defending land and territory. Just over half of these occurred in the department of Colón.

In total, between 2013 and 2023, 1,796 aggressions against women defenders were registered in the department, including harassment, threats, surveillance, and attempted murders. The trend is also worsening. While there were 146 incidents in all of 2022, the network recorded 505 incidents between January and September 2023. The main perpetrators of this violence are police, businessmen, and landowners who are often linked to organized criminal networks.

At the other end of the chain of violence produced by coca cultivation and cocaine trafficking, there is fear, which seduces, traps, and devours addicts.

On the plastic chair in the Comayagüela home, David replaced Ángel and White in our conversation. He is 32 years old, wears a navy-blue cap and smiles a lot. He proudly records three months without consuming alcohol nor crack. He tells us that he lived in the United States for a while and tried many drugs, but recalled having a certain “control” because they were “party” drugs and only for occasional consumption. Back in Honduras, the only drug available was crack, the cocaine of the poor.

“It’s much stronger and cheaper. You go crazy. You burn your lips in desperation, you sell everything to get it, there is nothing social, no partying. With the crack rock it’s just me and the drug. Nothing else exists in the world.”

In that world, David always had the acute feeling that someone was coming to kill him, to steal his money, or that the police were coming to arrest him. So, like his companions in the group home, he ended up saying what has become a general truth in Honduras: “By force, I became addicted to anxiety.”

This article is part of NarcoFiles: The New Criminal Order, a transnational journalistic investigation into global organized crime, its innovations, its tentacles, and those who fight it. The project, led by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) in partnership with Centro Latinoamericano de Investigación Periodística (CLIP), began with a leak of emails from the Colombian Prosecutor’s Office that was shared with InSight Crime and more than 40 media outlets around the world. Reporters examined and corroborated the materials along with hundreds of other documents, databases and interviews.

This investigation was carried out in collaboration with the Consortium to Support Independent Journalism in Latin America (CAPIR), which is led by the Institute for War and Peace Reporting (IWPR)