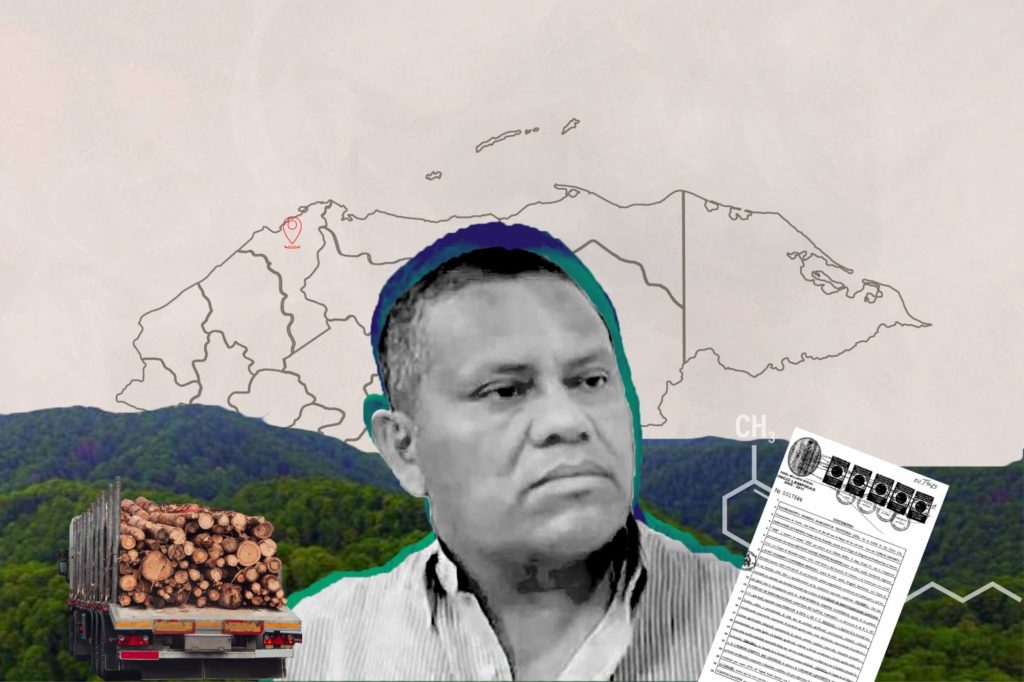

Geovanny Fuentes Ramirez used to be a businessman in the timber industry and an ambitious drug trafficker in Choloma, northern Honduras. He set up his own narcotics lab in the most remote region of El Merendón. There, with the connivance of municipal authorities, military and police officers, the support of a transnational Canadian company, and funding from an international bank, he created an illegal mine, a reforestation project, and illegally mortgaged more than 1300 hectares of land inhabited and cultivated by communities. Today, three years after Fuentes was apprehended, villagers still live under the threat of eviction because the same institutions that allowed this land dispossession deny responsibility.

Text: Célia Pousset

Editing: Jennifer Avila

Photography: Jorge Cabrera

Translation: José Rivera

English editing: Amy Patricia Morales

In the mountain range of El Merendón, also known by locals as “The Sacred Mountain,” north of Choloma, there is a large shadow that covers thousands of hectares and dozens of villages. This shadow, which instills fear in the population, has a face and a name, but it is not said out loud. Locals call him “the man” or “the one who went to Miami.” They often call him “he,” so one has to be certain it’s the same man.

Edwin is among the few individuals who openly mentions the name Geovanny Fuentes, possibly because of an unexpected visit Fuentes made to his home. It appears that Fuentes sought a warm reception despite being uninvited, yet insisting on purchasing Edwin’s property.

First meetup: The Tamarindo Mine

When Fuentes first met Edwin in 2012, he was with two bodyguards. Back then, Fuentes was not well-known, and people just muttered that he owned land in Cerro Negro, in the municipality of Choloma. No one said a word about drugs. Fuentes sat on Edwin’s sofa and told him that he wanted to buy his property to extract minerals. Edwin said someone else, Don Manuel, had already shown interest in buying the property, and had a contract already in place. Fuentes left but came back a few days later and asked Edwin to meet him in a restaurant in San Pedro Sula. Much to his surprise, Don Manuel was there with Fuentes and his brother, Cristian. They agreed that Don Manuel would get $18 for each ton of extracted minerals.

“After the meeting, I didn’t hear a word from Don Manuel. He never paid me. I don’t know what happened to him. Then, Fuentes trespassed without any notice into my property with his equipment and started to dig,” Edwin said.

He did not do anything because he thought he is the kind of person you do not mess with. Weeks later, Fuentes wanted to negotiate the price of minerals. They met on the property of Fuad Jarufe, a businessman who owned a rice-growing company in Choloma that laundered Fuentes’ money. Edwin was initially offered $4 per ton for six months, a deal he accepted. However, on the scheduled contract signing day, he noticed the terms were different – a 30-year validity period with compensation reduced to $1 per ton. This arrangement fell outside the country’s legal mining framework, lacking both a mining concession and an environmental permit.

Edwin remembers the lawyer who gave him that contract, Julio César Barahona, former judge and adviser in the Supreme Court. They testified against him in Fuentes’ trial. Fuad Jarufe’s accountant stated that Barahona had received 300,000 lempiras to hinder police investigations concerning Fuentes’ narcotics lab.

That day, Fuentes said, “Sign the contract if you want to.” Edwin signed, but he did not get a copy.

They searched for gold, iron, silver, and bronze nonstop. “Fuentes damaged the land,” Edwin said. On the strip mine, a man from the community that supported Fuentes agreed to talk to Contracorriente. He got 2,500 lempiras ($100) every two weeks for preparing food for mineworkers and police officers because “there were always two men who escorted him,” said the man, who hid weapons for Fuentes at his home whenever he asked.

“When I met the man he told me, ‘See that over there? Those rocks look very shiny, just like silver.’ I showed him some rocks from Edwin’s property, and then we went to a plot of land in Agua Blanca. ‘Man, you have everything going for you, I will give you a car and a gun.’ He came back 15 days later and asked his bodyguards ‘how do we pay him? We should kill him,’ said one of them. I got scared and looked at him. I noticed he was playing around with his gun. I felt like I was thrown off a cliff.”

One of Fuentes’ henchmen was president of the council in Jutosa, the largest village in this region near the side of the El Merendón mountain.

Fuentes was always armed and had political connections. According to U.S. prosecutors, he had AR15 rifles and 9-millimeter handguns. Another ally of his was the former mayor of Choloma, Leopoldo Crivelli.

“Crivelli came here with Fuentes. They were at my house and made me an offer regarding the minerals. I told Crivelli I didn’t have an extraction permit. He replied, ‘Don’t worry about it. We will give you 250,000 lempiras. We just need your name for the paperwork when the time comes to export minerals.’ You can’t use my name, I told him. Fuentes got angry and said, ‘Fuck, we can’t do business with you.’

During a phone interview, Crivelli denied helping Fuentes with his businesses, “I don’t go to the mountains; I am scared of heights. That’s why I don’t go there,” Leopoldo said when we asked him about his alleged visit to that region with Fuentes, whom he described as a “young man” from Choloma.

“His father was a friend of mine. I used to work for Fuad Jarufe. I am a rice expert and I managed a project in the outskirts of Choloma. And when I went to Jarufe to collect my two weeks’ payment, Fuentes was always there. We would often chat, but that is all. I am a public figure and I was mayor of Choloma for 16 years. You can ask anyone in Choloma who I am, and they will tell you. I have no connections to drug traffickers. I have never consumed cocaine and never owned a gun. I have always minded my own business. I did not smoke marijuana when I was young and that is Polo Crivelli’s word before God. I know nothing about this whole business,” he said.

Crivelli said he was “not aware of any investigations that proved Fuentes was a drug trafficker, but he seemed like a dangerous man who would not hesitate to kill. Everyone was afraid of him.”

Back then, when the mining negotiations were underway, many men were already under Fuentes’ influence. First, he bribed Leonel Rivera Maradiaga, leader of the Los Cachiros Cartel, by killing a mechanic who spoke badly of him. Just like a cat shows dead prey to its owner, Fuentes showed Maradiaga a picture of the mechanic’s corpse. Melvin Sanders, president of the soccer team Atlético Choloma, told Maradiaga that “it would be smart to partner with Fuentes; he could kill anyone if we ask him.”

Leonel Maradiaga denied his participation in the narcotics lab because he preferred to bring cocaine from Colombia and not manufacture it in Honduras. However, after that act of loyalty, Fuentes began transporting drugs from the Cachiro family to Juan Carlos “el Tigre” Bonilla’s ranch in Honduras. Bonilla is the former Chief of Honduran Police and is now awaiting trial in New York. Fuentes also transported drugs for the Valle Cartel, the most powerful cartel in western Honduras before they were brought down in 2014. Fuentes carried out his missions transporting drugs successfully and his narcotics lab in Cerro Negro was still producing between 200 and 300 kg of cocaine each month. To produce this amount, he hired two Colombians to cook the drugs and a dozen guards.

After the only raid in Cerro Negro in 2011, two murders took place in Choloma that echoed across communities as an act of retaliation.

The police officer who organized the raid was later kidnapped by Fuentes and his men. U.S. authorities stated that “the defendant and his confederates tortured the officer, hitting him in the face, and putting a plastic bag over his face to suffocate him. They put pins through the officer’s fingers […] The purpose of this brutal torture was interrogation: the defendant wanted to know if his money launderer and benefactor, Fuad Jarufe, had been implicated in the investigation relating to the Laboratory. After the defendant was satisfied that the officer had told them the truth about the investigation, the defendant killed the officer, firing three mercy shots to his head.”

According to U.S. prosecutors, nothing was found during the investigation because Crivelli’s son leaked information about the police investigation, and Chepe Handal, a drug trafficker from San Pedro Sula and collaborator in the narcotics lab, alerted them about the investigation.

Denis Muñoz was also murdered; he was a councilman in the mayor’s office in Choloma, and his property was next to Fuentes’ in Cerro Negro. According to villagers in El Merendón, Muñoz filed a complaint against Fuentes for environmental crimes, but to this day no one has been held accountable for that murder. In 2015, his son was gunned down and the case remains unsolved.

Regarding those violent deaths, Crivelli said, “I know nothing about that. I’m very friendly to other people and I would never do something like that.”

In March 2020, the DEA arrested Fuentes in Miami for trafficking cocaine. He was sentenced to life in prison by the Court for the Southern District of New York in February 2020.

In El Merendón, at the side of the road heading to Tamarindo, there is an abandoned house, which is completely destroyed. Locals say it is a shelter for evil spirits. However, in these parts, the specter of death is not just a legend. The man who worked with Fuentes on the mine used to say, “Those who refused to work with Fuentes live there.”

Second meetup: A reforestation project

“Judge, he’s 52 years old. He’s a citizen of Honduras. He was raised under humble circumstances in a violent country. He studied hard. He’s a high school graduate. He worked as a farmer. He started out in a rice production place where he was a rice sweeper. But he worked himself up, Judge. He worked in the textile industry for 26 years as a manager. He started at the bottom, worked his way up to the top. From 2013 and 2018, he had a biomass company. I’m going to call it a timber company,” John Burke, Fuentes’ lawyer, said during the trial as he introduced and defended his client. However, the Court found him guilty. Burke sought a 40-year prison sentence for his client.

Fuentes’ alleged respectable timber company was not respectable at all. In Honduras, he was indicted for environmental crimes and for using his company to register and mortgage land owned by farmers in El Merendón for generations.

Gustavo Mejía, the current mayor of Choloma and a member of the Libre Party who had been a councilman since 2014, said to Contracorriente, “we always regarded Fuentes as a timber businessman, and he was responsible for most of the deforestation in Choloma, according to authorities. We never thought he was a drug trafficker. He was not the eccentric type like many drug traffickers who show their guns and drink excessively; he kept a low profile, but who knows what he did in private. I knew him for his biomass business. Then, the most cunning thing he did was to get rich off land that did not belong to him. And he was backed up by municipal authorities.”

A few months before Fuentes mortgaged the properties, he met with residents of two villages in El Merendón, San Antonio de las Quebradas and La Jutosa, and offered to start a new project to develop local communities. That was the second time he approached the communities.

Don Rafa, leader of the Las Quebradas community, remembers quite well when Fuentes and Crivelli went to his house in 2012. Back then, they were already illegally extracting minerals in Tamarindo.

“A man introduced himself and said that he wanted to invest in plant nurseries to reforest the region. There was a meeting where I introduced myself along with two neighbors, and we listened to his offer. Three men—presumably lawyers—, Mayor “Polo” Crivelli and two well-armed men came to talk about the project. They said the project would help communities repair highways, build dispensaries, and provide good wages for those who work in the plant nurseries. The man said that they would build a school in Las Quebradas, and, in exchange, we had to plant trees because we could harvest timber from the forest.”

Fuentes wanted to grow a tree known as jumbay (guaje in Spanish). It is not a very sturdy tree and is often used as food for cattle. Rafa recalled asking him, “Why do you want to cut down the trees?”

That was a common business practice in Agroforestal Fuentes; to take advantage of highly biodiverse land and grind the trees to produce sawdust. Biomass is renewable energy generated when organic material is ignited, but there’s a difference between generating energy from waste (sugar cane, African palm tree, and roots) and from oak, mahogany, pine, silk-cotton, and conacaste trees.

In 2015, the Environmental Prosecutor’s Office in San Pedro Sula issued an arrest warrant and an injunction against Fuentes for “logging and illegal exploitation of timber for aggravated commercial purposes.” Fuentes was accused of environmental crimes in the municipality of Santa Cruz de Yojoa, in the department of Cortés, but not for crimes committed in Choloma. The Environmental Municipal Unit issued a report to the district attorney describing how Agroforestal Fuentes operated without a permit issued by the Forest Conservation Institute (ICF) on private property, “we determined that trees were being logged, placed in a wood grinder, and the sawdust was used to generate biomass and sold to a company called Gildan.”

Read document here

Gildan is a Canadian textile company that works with many sweatshops in Choloma. It also owns a boiler on the outskirts of the industrial city that generates energy. On the company’s website, they proudly claim to be socially and environmentally responsible, “we use energy and water responsibly and pay attention to any input and output in our work.” Agroforestal Fuentes was not just a provider of organic material; the company also took loans from Gildan.

We requested an explanation from Gildan but they did not reply. We sent emails to two female workers in the communication services in Canada but were ignored.

Luis Soliz, ICF Director, said, “the drug trade and money laundering have severely damaged our forest. We know that the biomass industry was a cover-up for money laundering. A higher than actual input was declared, and since it was all incinerated to produce energy, there was no control. There’s still no control because it’s a mess.”

Within the El Merendón mountains, rivers and streams wind through, sculpted by ridges and gullies. The inhabitants of local communities safeguard the forests, adamantly opposing any tree felling. Fuentes set up two plant nurseries in El Merendón, one in Jutosa and the other one next to the Tamarindo mine. “Some people from the community worked there cleaning and getting plants ready for sale. There were 50,000 plants in the nursery, but a quarter was planted and the rest was lost,” Rafa said.

The plant nurseries were a cover-up that allowed Fuentes and his employees to move around the region in El Merendón freely, drive up to Cerro Negro with bushes, and cocaine imported from Colombia—according to the injunction—and come down with tree trunks. “He used to drive by with well-armed men; he would bring wood from Cerro Negro on military trucks,” a farmer from Jutosa explained. That’s why Denis Muñoz filed a complaint against Fuentes and paid with his life.

Agroforestal Fuentes was established in 2008. Carlos Augusto Hernandez Alvarado, the notary who registered the company and director of the legal consultancy office at the National Autonomous University of Honduras in San Pedro Sula, said to Contracorriente, “It’s our job to register properties. Notaries don’t do background checks on partners who wish to start a business. If they comply with legal requirements, which are minimal in Honduras, they are allowed to.” While on trial in New York, Fuentes claimed his business operated between 2013 and 2018 and employed 30 permanent and hundreds of temporary workers. He said he made $70,000 a week in this business.

A former employee of Agroforestal Fuentes talked to Contracorriente and shared his experience, one he wants to “forget.” We met him in a shopping mall; he was uneasy and evasive and asked if cameras could record his voice. “I got out with my head held high. I wasn’t involved in anything. I wasn’t aware of anything. You know how it is,” was the first thing he said. He explained that they worked in groups of ten with chainsaws and other machines to grind wood. It’s very exhausting and dangerous work. “Sometimes we had to sleep outside.” They cleaned properties owned by wealthy landowners and bought organic material. He admitted that they later “took it too far cutting down pine trees” and “that wasn’t clean energy because trees were cut down.” He left the business because he had “a bad feeling about all of this.”

When we asked him about what he felt, he did not answer and simply said that he didn’t know anything. However, he slowly outlined a sketch of a violent and angry boss who used to hit his own guards. “They were military or former military; you could tell by the way they carried themselves,” he added.

“I asked God to let me out of this business and he miraculously did,” he concluded as he got up to leave.

Fuentes and his men were not able to work in San Antonio de las Quebradas because locals were against it. Back in 2013, the mine was a failure because they did not find the amount of gold and silver they had expected and the “reforestation project” was not successful. Fuentes then decided to steal the land of residents who refused to give it away.

Mortgages and property fraud

Between April 2013 and May 2014, Fuentes obtained four lines of credit and mortgaged properties in El Merendón, Choloma. Banco Promérica granted the mortgage for a total sum of 92 million lempiras.

The following communities were affected: El Ocotillo, El Majaine, Planes María, San Antonio de Las Quebradas, El Tamarindo, Agua Blanca, Chachahuala, and El Chorrerón, where hundreds of people live.

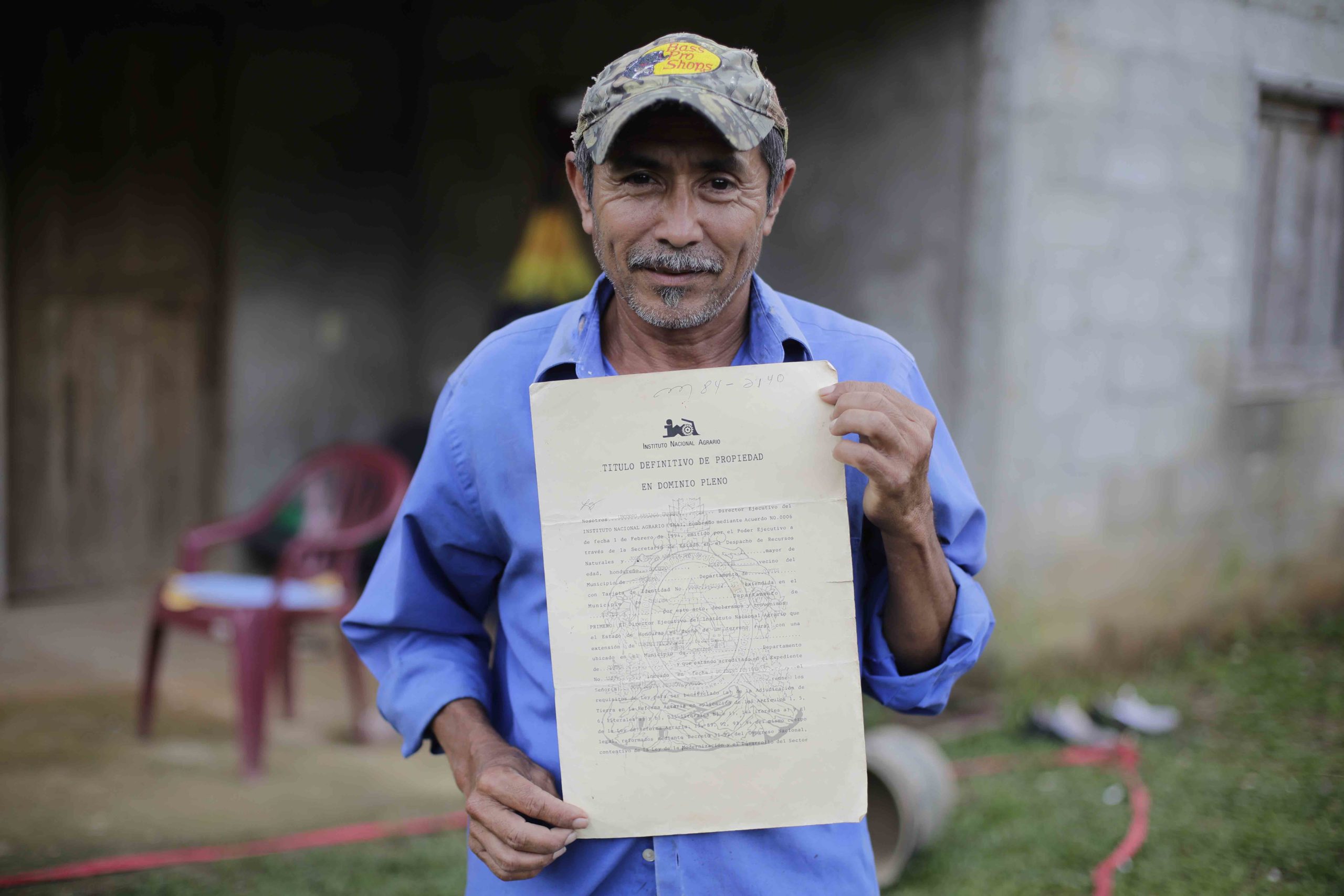

It was until March 2021 that locals realized their properties were encumbered. “We discovered in the Gaceta (the government’s official newspaper) that the entire region was put up for auction on March 25, and the properties now belong to the bank,” said a 50-year-old farmer from El Majaine whose property was mortgaged in September 2013.

“We have no idea how our land was taken by someone else, but the person who mortgaged our land needed approval from the municipality to register the land as his own. Property deeds had to be forged because we’ve had the original ones for many years. I got mine from my grandfather. My father inherited all of his land; it’s 29 blocks. But we’re screwed if they send the military or if another drug trafficker buys the land. Anything can happen because people don’t want to leave.”

In January 2013, a few months after the land was mortgaged, José Ulises Guevara was murdered. He worked in the mayor’s office and was in charge of the land registry in Choloma. Locals in El Merendón believe Ulises didn’t take part in any corruption schemes.

In Honduras, a very strict process has to be followed to register properties: a contract of sale, a legal title of ownership, and the property has to be registered in the Land Registry, so there’s a record that a property deed was issued.

According to locals, land registered by Fuentes’ company was backed up by the Municipal Corporation, and these properties were later registered in the Land Registry.

The first mortgage by Banco Promérica for 3 million lempiras to guarantee a line of credit includes two pieces of land in Cerro Negro, previously donated by Jarufe to Fuentes, and several properties in Río Blanquito. The second mortgage was for 7 million lempiras and includes more than 1,000 hectares in El Chorrerón, El Tamarindo, and Majaine. The third mortgage was for 9 million and includes more land and two wood grinding machines. There was one last mortgage, a biomass supply contract signed by the Canadian transnational Gildan, for 73 million lempiras.

Read documents here

One day after finding out about the auction, Rafa, a community leader in San Antonio de las Quebradas, went to the municipality of Choloma to look at the map of registered properties and check which properties were mortgaged. “The agent at the Land Registry office told me ‘your village is not on the list.’ I said I wanted to see the map. I found out my property would be put up for auction,” said Rafa, who owns four hectares of land and holds the property deed issued by the National Agrarian Institute (INA) in 1995.

“This is my land. I’m the sole owner of the property that was mortgaged. How is that possible? But thank God we still have the forest,” Rafa said, expressing consolation.

The foreclosure took place in 2018 because Fuentes and his joint guarantors, Frederick and Fuad Jarufe, did not pay. It was a long process because the judge claimed Fuentes’ address was not known and he couldn’t be notified. Maribel Espinoza, a lawyer whose law firm represented the bank, said to Contracorriente that the process was abnormal and difficult, probably because of the collusion between the civil court in Choloma and Fuentes. “The city court ignored regulations that ensured the debtor would be notified of any legal processes to his current address or in case he changed his address. This bought the debtor time to avoid the auction where mortgaged properties were being sold,” she said.

Finally, one year after Fuentes’ arrest, the judge in Choloma announced the auction.

In view of having their land sold by auction, around 300 people from communities in El Merendón protested in front of the bank in San Pedro Sula. The bank manager suggested three people go into the building to talk. They refused and replied, “We either all come in or no one does.”

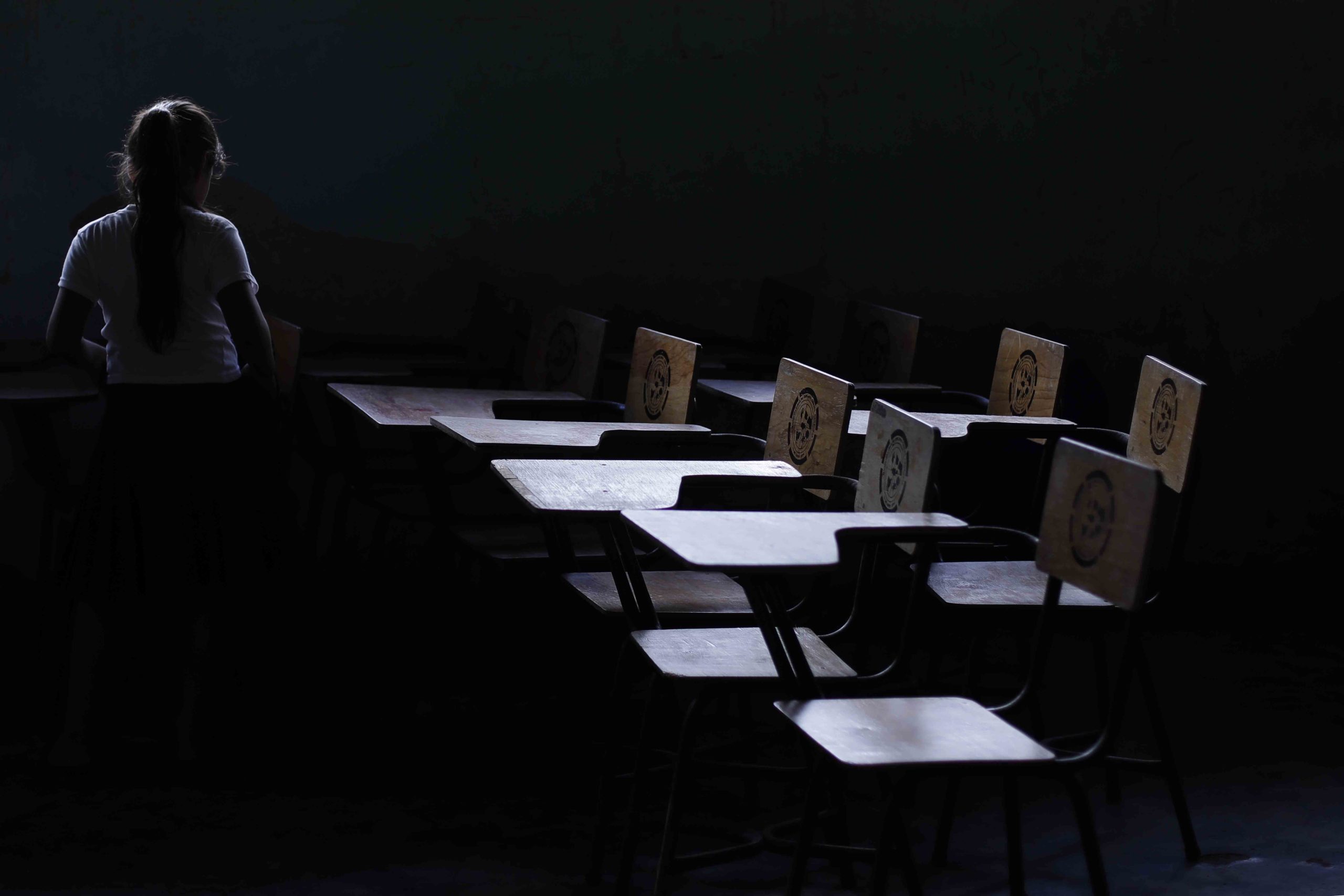

On that day, March 25, there were no bidders. The judge granted ownership of the properties to the bank which are valued at $717,623.98. Communities live under the threat of eviction ever since.

“Life is kind, but we know if they threaten us at gunpoint, we have to leave,” said Rafa on his patio. His house is right in front of Lempira, a school built by the community without any help from Fuentes.

Fuentes’ arrest

The arrest of a drug trafficker marks just the beginning, not the end. In some capacity, whether directly or indirectly, Honduran institutions, including the police, military, municipal, or judicial, and transnational companies such as Gildan, and the banking system, were involved in criminal activities committed by Fuentes. “Americans are interested in confiscating drugs and we should be interested in improving our own country and reforming our corrupt institutions, that’s our duty. Not every issue is going to be solved in the U.S. It’s important that we do our part and deal with corruption,” said Carlos Paz from the Cáritas en Honduras mission, an organization the communities in El Merendón turned to for support.

Contracorriente contacted a source in the mayor’s office in Choloma who remained anonymous and repeated a dozen times, “I stayed out of many things that were going on.” That person also denied the mayor’s office was involved in granting property deeds to Fuentes. “We talked about it in the municipal council, but we were never involved. I think it was a collusion between the government and the Institute of Forest Conservation that led to schemes in the Land Registry, but the municipality was not aware of this.” Our source defended the institution, but also claimed, “we had to keep our mouths shut since we know how things are,” suggesting that the whole situation was not so clear. “What was going on internally was complicated. The head of the Land Registry and a city councilor were murdered. A lawyer had to flee Choloma because he wouldn’t tolerate this kind of corruption.”

Our source finally said the issue was caused by Banco Promérica because they allow property to be mortgaged under irregular conditions.

We contacted the bank and asked under what conditions did Fuentes mortgage those properties and if an inspection took place to verify that he owned the 1,000 plus hectares of land. They replied, “The loan was granted in accordance with current credit policy and rules and regulations established by the National Commission of Banks and Insurance. A valuation was done in compliance with banking regulations and the bank’s policy. As part of the bank’s processes, we verified at the Land Registry guarantees brought forward by clients to verify they were the legitimate owners.”

Verification was not very thorough and the Land Registry has been under scrutiny for being plagued by corruption. José Cardona, president of the board of directors and Secretary of Social Development (SEDESOL), blamed the nationalist governments since “they tolerated corruption on issues of land regularization to benefit drug traffickers. Many mayors granted property deeds to anyone who paid them and didn’t care if people lived there. Property deeds were granted even though legitimate owners had the original ones. Files went missing. There’s no governance to avoid granting property deeds twice and to prevent bribery. This mess is one of a kind in our history, and we can’t solve it in four years,” he argued.

We went to the National Property Management System and looked up records of properties mortgaged by Fuentes to understand how he became the owner, but there is no record of previous owners, with the exception of a piece of land given away by Fuad Jarufe. An employee from the Property Regularization Office commented, “We couldn’t verify who the previous owner was, but we noticed Fuentes submitted property deeds in 2013. These documents can only be obtained from a municipality.”

Only a municipality can issue property deeds, but according to former Mayor Crivelli, they were not issued by his office, “I was the mayor and they are my neighbors. How could I allow this? How could I steal land, which I had not seen, that belongs to someone else to benefit this man? I don’t know how he registered those properties as the owner. I first heard about the mortgages when the auction was taking place. There are rumors he financed my political campaign and gave me 220,000 lempiras, but thank God that never happened. I have been dragged into this issue and people in politics don’t mean well, that’s one reason I lost the elections. I don’t know what the documents in New York say, but it’s all made up. Claims from random people are not necessarily true. You can come here and investigate. I can take you there, even though I am no fan of heights.”

Crivelli lost his fourth reelection, but his daughter, Katia, was elected as congressional member for the Liberal Party, which is led by Yani Rosenthal, a politician who served time in prison in the U.S. for laundering money from the drug trade.

Gustavo Mejía, the current mayor of Choloma, promised to help communities in El Merendón during his campaign, but he is shifting the responsibility to solve the problem to Congress. During the interview, he called Iris Pineda, a congressional member of the Libre Party, to whom he claims a report on the case was sent.

—No, Tania [Head of the Environmental Department in the mayor’s office] has the report, Pineda said.

—Well, Tania said she gave it to you.

—I don’t know. I would have to look for it among the pile of paper I have at home.

—Well, then look for it.

In the meantime, communities live under constant threat of eviction. We asked the bank about the future of communities living in those properties, and they replied, “There are no offers at the moment. When offers start to come in, we will analyze the situation.”

“You know what’s ironic? We still pay taxes to the municipality,” Rafa said.

When it was time to leave the mountain, as it was getting dark and farmers were leaving the fields to go home, we came across a man on a white horse. His boots were covered in dirt. He said his name was Ezekiel. He talked about politics, religion, and money, three tools of oppression. He knows the story of the mine, Fuentes’ company, and the mortgaged properties. But as we tried to understand his view of the situation, he glanced at us one last time before leaving and he laughed a bit and said from on top of his horse, “That’s how it’s always been, but, you know, here the struggle is born and grows in blood. It’s what we have.”

This investigation was possible with support from the Consortium to Support Independent Journalism in Latin America (CAPIR), which is led by the Institute for War and Peace Reporting (IWPR).